By Olga Tokariuk

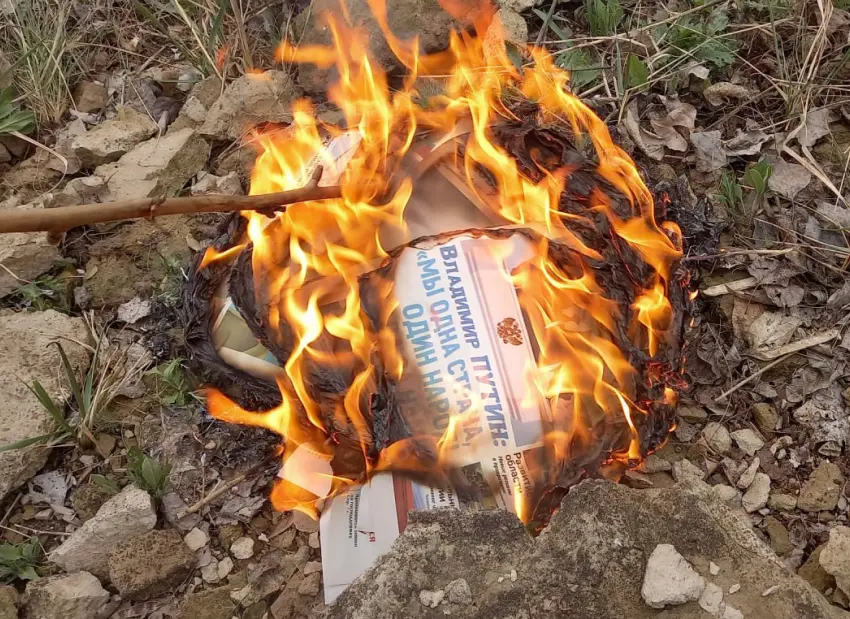

Ukrainian resistance to Russia’s full-scale invasion occurred not only on the battlefield, but in the information space as well. Russia has been conducting wide-scale disinformation and propaganda campaigns against Ukraine in the last ten years, seeking to undermine Ukrainians’ unity and their support by the West. It has also been trying to impose its imperialist vision of Ukraine as ‘not a real country’ that doesn’t have a right to exist as an independent state. Humour has become an important tool for Ukrainians in their non-violent resistance to Russian disinformation and imperialist ideology

Ukraine’s history of using humour as a manifestation of resistance

Ukrainian literature – and culture in general – is full of examples of using humour in adverse times. One historical example of it is Ivan Kotliarevsky’s “Eneida”, a burlesque epic poem and satirical interpretation of Virgil’s “Aeneid”. It was the first literary work in the modern Ukrainian language, published in 1798 in Tsarist Russia, which controlled parts of modern-day Ukraine. Ukrainian was widely spoken by the local population, but the publishing of books and education in Ukrainian were restricted in the Russian empire and ultimately banned in 1873.

Kotliarevsky showed that the Ukrainian language is not just a vernacular dialect, but is well suited for creating major literary works. This was hugely empowering for Ukrainian speakers and gave rise to a whole literary tradition. What on the surface seemed to be the story about Ancient Greece and the destruction of Troy, was in fact a story about the destruction of the Ukrainian cossack republic Zaporiz’ka Sich at the hands of Russia’s Catherine the Second. Kotliarevsky’s ‘Eneida’ used humour to express anti-imperialist sentiment and ridicule Russia’s tsarist regime.

‘I laughed in order not to cry’, wrote Lesia Ukrainka, a famous early 20th century writer, in one of her poems. Humour helped to keep people’s spirits up over Ukraine’s turbulent history, which just in the 20th century was marked by five attempts to proclaim independence, two world wars, Stalin’s artificial famine Holodomor and communist repressions, all of which killed millions of Ukrainians.

In Soviet times, humour was an important tool used by members of Ukrainian anti-communist resistance. In the 1940s, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) published an underground magazine ‘Ukraiyinskyi Perets’, where it ridiculed Stalin, Hitler and life in the USSR in general.

In a totalitarian state like the Soviet Union, it was life-threatening to openly criticize or even subtly ridicule the regime. Ukrainian writers and satirists who dared to do so were either killed, sent to labour camps, or eventually co-opted by the state into becoming communist mouthpieces who used humour for propaganda purposes, like ridiculing ‘bourgeosie’ or ‘enemies of the people’. In Soviet times really funny jokes were mostly told in citizens’ kitchens.

Humour as a response to Russian invasion of Ukraine (2014-2022)

After Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine in 2014, which manifested itself in the occupation of Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, Ukrainians realized they were dealing with a hybrid attack: not only military aggression, but one in information space as well. Using propaganda and disinformation, Russia tried to undermine Ukrainians’ unity, trust in institutions and desire to defend their country. Russian disinformation campaigns were designed to convince global audiences that Ukraine wasn’t a real country, that it was highly corrupt and divided, essentially ‘a failed state’ not worth supporting.

Back in 2014, Ukrainians realized they did not have enough resources to compete with a well-funded, omnipresent Russian propaganda machine with access to foreign audiences via outlets such RT, Sputnik etc. They needed a creative, cost-effective approach to counter Russian information attacks. Humour was one of the solutions.

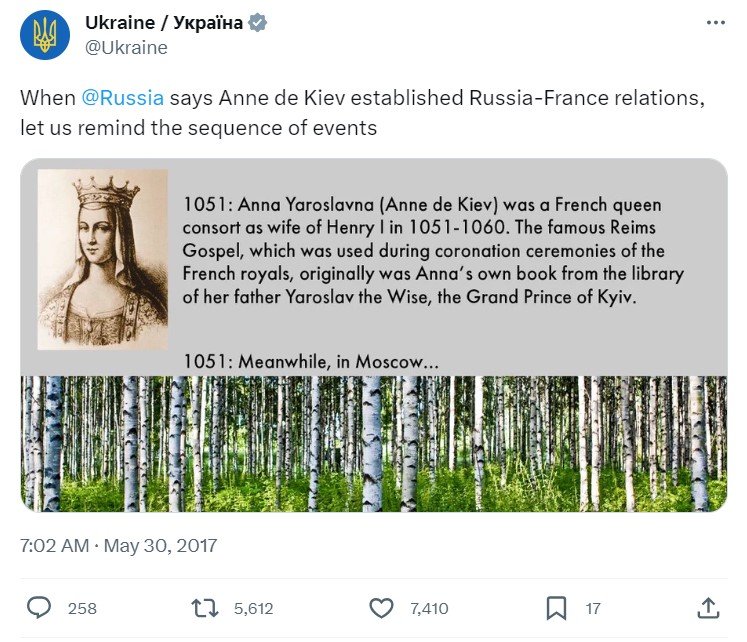

In 2016, Ukraine launched its official Twitter account, which widely used jokes and memes to introduce the country to international audiences and combat Russian propaganda. As its founder, Yarema Dukh, said, ‘We understood we would never have budgets similar to those Russia has for its propaganda and disinformation machine. Creating state-sponsored media didn’t look like the right way to go either. So our idea was to reach the widest audience with information about Ukraine, having a very small budget’. Currently, Ukraine’s official Twitter (X) account has 2.2 million followers, with some of its humorous tweets becoming truly iconic.

A great example of how @Ukraine account used humour to dismantle Russian imperialist narratives is an exchange of tweets about Anne of Kyiv, XI century Kyiv Rus princess married to the French king Henry I.

Starting with a tweet debunking the Russian president’s attempt to appropriate this historical figure as Russian, Ukraine’s official Twitter account was then able to tell the story from the Ukrainian perspective – and mock Russia for trying to appropriate the legacy of Kyiv Rus, which existed long before Moscow was founded.

One of @Ukraine’s founders Yarema Dukh says that a feature of humorous content is not just to make people laugh, but ‘to tell the history of Ukraine, to present our point of view, to remind people of the war and Russians’ actions’.

Use of humour to counter Russian disinformation since 2022

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022, humour has been used by many actors in Ukraine to get the message across about the Ukrainians’ bravery, resilience, commitment to freedom and democracy. Several acts of resistance that involved humour and ridiculed the enemy became powerful symbols of the Ukrainians’ outstanding courage in the face of a presumably much stronger enemy.

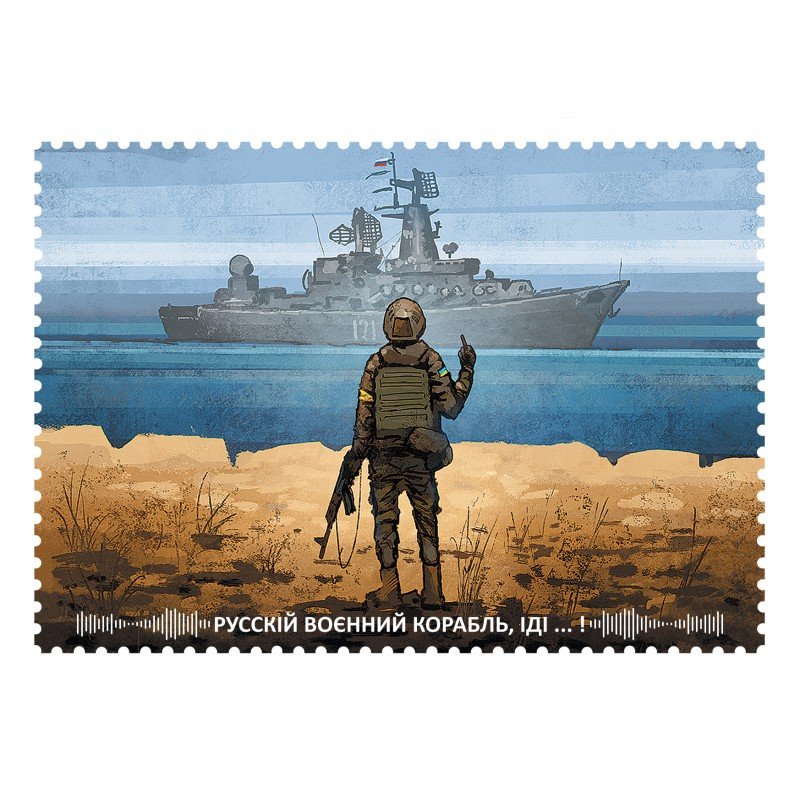

One is a conversation between a Ukrainian border guard on the Serpent island in the Black sea, and an officer from an approaching Russian military warship, demanding Ukrainians’ surrender. ‘Russian warship, go f..ck yourself’: this answer by a Ukrainian border guard immediately became a meme, later used on postal stamps and various memorabilia.

Another symbolic act of resistance was captured on video in Henichesk, southern Kherson region, which Russian troops occupied in the first days of the invasion. The local population organized protests and didn’t hesitate to show their attitude to the invaders. ‘What are you doing here?’ – a Ukrainian lady is asking a Russian soldier in a video that went viral. ‘You are invaders, you are fascists… At least put some sunflower seeds in your pockets so that something good can grow out of you when you die here’. This conversation was a powerful demonstration that Ukrainians, even in Russian-speaking Southern parts of the country, were not willing to live under Russian occupation.

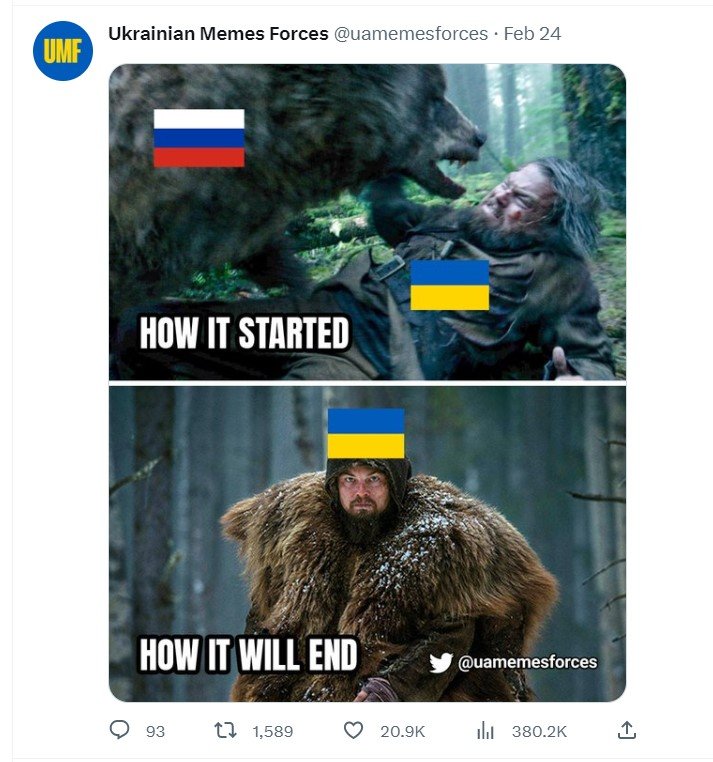

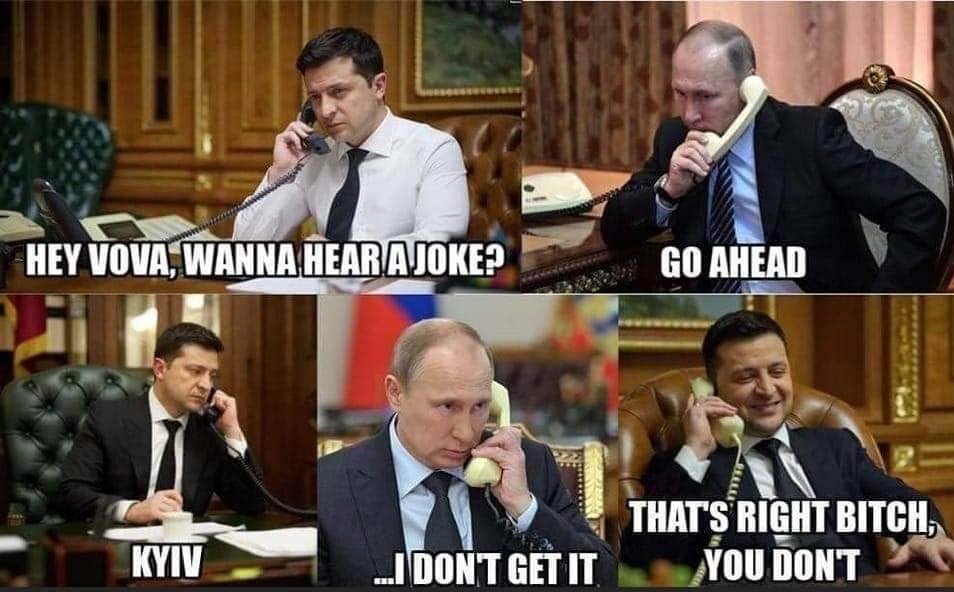

A lot of humorous content was produced by social media accounts, such as Ukraine Meme Forces on X. Their memes often used references to Western popular culture to connect with audiences abroad.

Another phenomenon, NAFO – North Atlantic Fella Organization (a word play with NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization), was also born on X: a ‘shit posting, Twitter-trolling, dog-deploying social media army taking on Putin one meme at a time’, as described by Politico. Twitter cartoon dogs exposed lies of Russian officials and ridiculed Kremlin’s disinformation about Ukraine and the war, while raising money for the Ukrainian military.

Ukrainian officials widely use humour in their communication with foreign audiences to mock Russia and underline Ukrainians’ bravery.

Here is a joke that president Zelensky – whose background is a comedian – told the TV presenter David Letterman when interviewed by him.

“Two Jewish guys from Odesa meet up. One asks the other:

‘So what’s the situation? What are people saying?’

‘What are people saying? They are saying it’s a war.’

‘What kind of war?’

‘Russia is fighting NATO’.

‘Are you serious?’

‘Yes, yes! Russia is fighting NATO.’

‘So how’s it going?’

‘Well, 70,000 Russian soldiers are dead. The missile stockpile has almost been depleted. A lot of equipment is damaged, blown up.’

‘And what about NATO?’

‘What about NATO? NATO hasn’t even arrived yet.”

Humour is also used to raise money for Ukraine. Saint Javelin project, launched by a Canadian-Ukrainian former journalist Christian Borys, creates memes online and manufactures merchandise with them. The most popular one is the brand logo, Saint Javelin of Ukraine: an icon-style picture of Virgin Mary holding a Javelin portable anti-tank missile (one of the first Western weapons supplied to Ukraine). Since its creation in early 2022, Saint Javelin has raised and donated over $2 million to Ukraine.

Saint Javelin promptly reacts to social media trends and thematic issues collections. After the Ukrainian strikes on illegally built Kerch bridge, that links occupied Crimea to Russia, they released a ‘Crimea Beach party’ collection, and their most recent staple are baseball caps ‘MUGA’ (Make Ukraine Great Again) sign – a mocking reference to the US politician Marjorie Taylor-Green’s attempts to stop Ukraine aid.

Why humour is efficient in non-violent resistance

Humour is an internal uniting factor and a coping strategy: For Ukrainians, using humour is an excellent coping strategy in the situation of ongoing tragedy. Life goes on even during war, as Ukrainians found out, and mental health needs as much attention as physical health. Jokes and memes that people share on social media help to foster a sense of unity and belonging, and to cope with the terrible reality of war. Gallows humour is particularly helpful in that regard.

Humour helps to reach wider audiences and raise awareness about an issue: ‘Comedy is very disarming, you talk about sensitive issues in a very disarming way that you cannot if you’re making them serious’, Priyank Mathur, former scriptwriter for The Onion said. ‘The content most likely to go viral online is humorous, human beings like that, they like sharing it even more than angry content. It’s fun, it’s a way of bringing new audiences into the discussion’.

Researchers argue that humour can also be an important tool to raise awareness about disinformation. According to Jakub Kalensky from Helsinki-based Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats and his ‘four lines of defence’ against disinformation principle, humour can serve as a second line of defence: raising awareness about an issue among the general public.

Humour is a soft power tool that helps win other people’s hearts and minds: Showcasing Ukrainians’ bravery in resisting Russian invasion, their resilience and creativity, in spite of the atrocities of war, helped to evoke solidarity across the world. Corneliu Bjola, Associate Professor of Diplomatic Studies at the University of Oxford, sees three distinct features of Ukrainians’ use of humour in their digital diplomacy: 1) to undermine the perception of Russia and Russian army as a superpower; to ‘dilute’ its threats and nuclear blackmail; 2) to introduce Ukraine to Western audiences in a positive way; 3) to decentralize the use of humour: it wasn’t mandated by the government, but was often bottom-up, spontaneous and funny.

Ridiculing the enemy/adversary makes it less scary, helps to counter fears: In the first days of war, humour helped many Ukrainians to overcome a sense of panic and fear. It highlighted failures of the Russian army which turned out to be not as strong as many have expected. As Ukrainian psychologist Svitlana Royz wrote, ‘we laugh together and it unites us. We were afraid, and now we ridicule [Russians]. We lower our tension. We alleviate our pain. We try to take back control with the help of humour and jokes’.

Humour and satire help to expose the absurdity of Russian imperialist narratives: In Ukraine’s strategy to counter Russian propaganda and disinformation, humour has been often used to ridicule and expose the absurdity of Russian narratives. Putin’s failed intention to take Kyiv in three days generated a ton of memes. Countless jokes were produced to mock Russia’s ludicrous claims about the need to ‘de-Nazify’ Ukraine or that Ukraine was not a real state. Humour helped to highlight the absurdity of Russian imperialist ideology in a funny way.

Humour is a gateway to a bigger story and a vaccine against fatigue: Behind every joke or meme, there is a story to tell. Humour gives a possibility not only to make people laugh, but to talk about the bigger picture. In the case of Ukraine, it helped to spark the audience’s interest in the context and desire to learn more about the country, its history and culture. Humour is also a tool to combat war fatigue. Nadiya (real name changed at her request), who is making content for Ukrainian officials’ social media accounts, says: ‘Russians get angry because you are showing them you’re not afraid, you’re laughing your enemy in the face. And to foreigners, you are demonstrating your confidence in this way. Our main message from the beginning is: Ukraine is able to win, so your support must not stop. It is like saying: see, Ukraine is winning in communications, so it can win on the battlefield too’.

Conclusions

Ukrainians resorted to humour during various turbulent periods of their history, and they use it as a powerful tool of non-violent resistance since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in 2022. Humour helps Ukrainians to cope with war trauma, to feel unity and fend off fear. In their communications with the outside world, humour is a useful tool to mobilize support, to ridicule Russia’s military might and undermine its threats. Ukraine uses humour and satire to expose Russian imperialist attitude: by ridiculing it, undermining it, questioning its power and authority.

Ukrainians’ use of humour is peculiar in a sense that it is not centralized, it is not mandated or initiated by the government (although officials use it too). The way Ukrainians use humour reflects the nature of modern-day Ukraine: a democratic, freedom-loving country with a strong and vibrant civil society that is taking the initiative and comes up with creative and efficient forms of resistance, that refuses to be intimidated and laughs its enemies in the face. Ukraine’s use of humour is yet another example of how different it is from Russia, with its pathetic propaganda attempts to produce humorous content.

Olga Tokariuk is a Ukrainian journalist and Chatham House Leadership Academy Fellow with Ukraine Forum. This article is based on her research paper on Ukraine’s use of humour to counter Russian disinformation for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Read also