Natalia Pozniak

“To build non-violent resistance, you must have way more strength than to seize everything by force,” said Yevhen Sverstiuk, the distinguished Ukrainian dissident. For Ukrainians, at various times in history, it was the non-violent resistance that became a source of strength and self-determination, which made the preservation of identity and survival as a people possible in times when the state was non-existent.

“Each to their own for their own”

Adherents of non-violent resistance trace its origins to the philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King. But long before that, Ukrainians were displaying amazing examples of self-organization and cultural resistance that enabled them to counter assimilation, preserve their traditions, and maintain a strong voice in their communities.

The tradition of non-violent resistance in Ukraine reaches back far earlier than the modern usage term itself, which is still evolving, as are the methods and tactics of such resistance.

XVI-XVII centuries. Ukraine confronts the political and religious expansion of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Polish landowners had a major say in politics, and higher education was aimed at Polishization and Catholicization. That is when the Brotherhoods – associations of Orthodox citizens – started to emerge, funding Orthodox churches and education with their own means. Among other things, by opening up the so-called Brotherhood schools, which were becoming a model of democracy and human equality at the time.

The school accepted people of all classes; children from impoverished homes were given financial aid, orphans were fully cared for by the Brotherhood. Some of the greatest patrons of the Brotherhoods were Zaporizhzhia Army officers and hetmans, such as Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachnyi. In 1632, the unification of the Lavra and Kyiv Brotherhood Schools gave rise to the Kyiv-Mohyla College (later the Academy), one of the largest and most prominent educational institutions in Eastern Europe at that time.

The same kind of self-organization and community support helped Ukrainians to avoid assimilation in the XIX century. Ukrainian intelligentsia revived Sunday schools, including those in the countryside, the “Khlopomany” movement and Kyiv’s “Hromada” emerged. After the Russian Empire outlawed the Ukrainian language in the cultural and public sphere, including publishing, on the grounds that it “never existed,” “does not exist,” and “cannot exist,” the “Hromada” remained in close contact with Halychyna, still publishing in local publications, organizing rallies and cultural events. After 1905, as the imperial administration’s grip weakened slightly, the “Prosvita” [Enlightenment] societies, choirs, and amateur theater groups in Ukraine began to emerge in large numbers, which also served as spontaneous resistance to total Russification.

The Chlopomans movement was very important in public education and in preserving identity.

Photo: Tadei Rylsky and Volodymyr Antonovych in a circle of like-minded people. Source

Another method of nonviolent resistance, this time to economic oppression in Ukraine, was commercial cooperation among Ukrainians. In the late XIX century, in Halychyna, with all trade concentrated in the hands of the Polish aristocracy and wealthy Jews, the phrase “Each to their own for their own” quickly became popular. Business became not merely an economic activity, but also a step towards national solidarity: mutual aid societies were formed, where people shared what they could, and helped those in need. Cooperation stopped the emigration flow to Canada and the United States, and by the 1920s, the products of the Maslosoyuz or Tsentrosoyuz cooperatives were selling in both Europe and America.

Also involved in the cooperative movement were the business and cultural elites. Therefore, even in times of a harsh pacification policy carried out by Poland in mid-war Halychyna, Ukrainians remained resilient. Non-violent resistance was ultimately suppressed only with the rise of the Soviet regime.

Ukrainian cooperative products were very popular in Europe and America.

Photo: A Maslosoyuz shop in Lviv. Source

“Freedom virus” against the system

In the XX century, it was self-organization that enabled Ukrainians to stand tall, and even reclaim their statehood for a brief moment. Among the first peaceful displays of national feeling was the Freedom Day celebration in Kyiv on April 1, 1917, when over 100,000 Ukrainians flooded the city’s streets upon the request of the newly formed Centralna Rada. It was a remarkable feat for the provincial Kyiv, where only three noble households – the Lysenko, the Kosach, and the Starytskyi families – spoke Ukrainian just ten years earlier.

“Each of those demonstrators, as they drifted off to sleep that night, envisioned hundreds of yellow-and-blue banners fluttering in the rapid gusts of wind towards the clear skies, as if screaming of our might and tenacity. And waking up in the morning to his daily routines, any conscientious Ukrainian was no longer alone and marooned, for he was now confident a hundred thousand like-minded, freedom-fighting brothers and sisters walked with him, shoulder to shoulder,” wrote the new Ukrainian student magazine Sterno.

Mass peace rallies were the late-1920s expressions of resistance against the collectivization in Ukraine. Farmers exited their communal farms, took their property, and freed their imprisoned fellow villagers. Women actively participated in these protests, which is why the Bolsheviks dismissively referred to them as “women’s riots” or “bagpipes.” In 1930, about 4,100 mass protests against the regime were organized in Ukraine, attended by over 1.2 million people.

The Holodomor and large-scale repressions initiated by Stalin in Ukraine and other occupied territories made any form of non-violent resistance impossible. To even publicly voice disagreement with the Communist Party’s policies entailed arrest and execution or years of hard labor in the Gulags. But as soon as Stalin died, his personality cult was denounced and ideological pressure was alleviated – Ukrainians’ aspirations for truth and freedom were once again in ascendance.

Mass riots that broke out across the Gulags in 1953-54 were in part triggered by Ukrainians, particularly convicted members of the OUN and UPA. Non-violent resistance, including strikes, disobedience, and the fight for basic rights, played a significant role in those uprisings. The system violently punished the rioters in Kengir, Vorkuta, and Norilsk, however, the “freedom virus” spread, eventually leading to the collapse of the camp system. In 1955-1956, a gradual revision of the prisoners’ cases began, resulting in reduced sentences and early release. In 1960, the Gulag system was decommissioned.

The Kengir uprising was suppressed by tanks that attacked columns of unarmed women.

Photo: painting ‘Blood of Kengir’ by Yuriy Ferenchuk, 1993. Source

This “freedom virus” spread to society. In 1960, the Contemporary Youth Club “Sovremennik” emerged in Kyiv, bringing together young poets, theater artists, and scholars. Independent and uninhibited, they revived Ukrainian traditions, keeping alive the memory of the “Executed Renaissance”, unveiled the truth behind the Bykivnia gravesites. Clubs like this were founded in other towns and cities of Ukraine.

The CYC functioned for 4 years, with arrests of its prominent figures a year later; Ivan Svitlychnyi, Opanas Zalyvakha, the Horyn brothers, Valentyn Moroz, Sviatoslav Karavanskyi were detained. This did not deter the future dissidents, but only pushed them further down the path of protest. On September 4, 1965, at the film premier of “The Shadows of The Forgotten Ancestors”, Ivan Dziuba took the microphone to speak on the arrests of the wayward intelligentsia. Many in attendance stood up in protest.

More arrests of those against the Communist doctrine will follow, with more redundancies and other forms of pressure. Some will be forced into public repentance and apologies once they’ve been sacked, like Ivan Dziuba and Oles Berdnyk; some will be assassinated – Vasyl Symonenko and Alla Horska are among those many killed by the state. The “freedom virus” cannot be stopped though, the non-violent resistance has become one of the common means to fight the regime.

It takes many forms. Samvydav [self-publishing] becomes increasingly popular: typewritten texts about the real Ukrainian history, human rights violations, and the state of culture, as well as controversial articles on the subject such as Ivan Dziuba’s “Internationalism or Russification” or Viacheslav Chornovil’s “Trouble from the Mind”, are passed from hand to hand. Open letters of support for political prisoners signed by dozens of people are widely circulated.

In 1968, Vasyl Makukh committed an act of self-immolation on Khreshchatyk, protesting against the Soviet troops invading Czechoslovakia. Ten years later, on the Chernecha Hora in Kaniv, Oleksa Hirnyk lit himself on fire to protest the annihilation of the Ukrainian language.

In 1976, the writer Mykola Rudenko, the General Petro Hryhorenko, and eight other dissidents put together the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, the first legal organization in the USSR to fight human rights violations. It was a near-suidical undertaking, and they were immediately given with harsh prison sentences; four of them died in the camps, and one committed suicide before the arrest.

Yet they won. New people stepped in to replace those arrested and imprisoned. By the end of the 1980s, the Ukrainian Helsinki Group released 30 memoranda, declarations, manifestos, appeals, and newsletters – all dedicated to the problems of political, economic, and spiritual specificities of Ukrainian people, along with the safeguarding of human rights. In the end, the UHG was one of the reasons why the Soviet Union collapsed.

The Sixties movement, which became the foundation of the Ukrainian dissident movement, began with the revival of folk traditions.

Photo: Vasyl Stus with participants of the nativity scene at the Sadovski house, Lviv. 1972. Source

From Maidan to Victory

Ukraine’s recent history shows how non-violent resistance has played such a crucial role in showcasing the unified strength of the nation. The word “Maidan” is now forever engrained in the collective psyche as a symbol of a united people against dictatorship. The last three non-violent revolutions have drastically changed modern Ukraine – irrevocably.

1990. The Student Revolution on Granite. For over two weeks, a student hunger strike protesting the signing of a new Union Treaty and demanding other democratic freedoms took place on what was then October Revolution Square. The administration was forced to give in: Prime Minister Vitalii Masol resigned, and other concessions were made, notably that Ukrainian males were allowed to perform their military service on Ukrainian soil. Still, the students’ main demand: for re-elections to the Verkhovna Rada [Ukrainian Parliament] was not satisfied.

The Student Revolution on Granite was the first successful mass act of non-violent resistance in the late USSR, a precursor to the declaration of Independence.

Photo: participants of the student hunger strike. Source

2004. The Orange Revolution. For one month, Ukrainians protested in the city center of Kyiv in favour of pro-Ukrainian candidate Viktor Yushchenko and against election fraud that had cheated him out of victory in the second round of the Presidential elections. Ultimately, a third election round was announced, with Yushchenko prevailing. This revolution disrupted Russia’s plans to turn Ukraine into another Belarus back in 2005.

2013-2014. The Revolution of Dignity. For three months, Ukrainians confronted the regime of Viktor Yanukovych. It began with peaceful protests against Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the EU Association Agreement and, as the regime became violent, escalated to fighting on the Hrushevskoho Street, and the shooting of many protestors, eventually named the “Heavenly Hundred”. The people won. Yanukovych defected to Russia. In response, in early 2014 Russia launched a military campaign that has been ongoing ever since. The Revolution of Dignity gave rise to another present-day phenomenon – the volunteer movement, which has become a major factor in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

There have since been many more “Maidans” and acts of civil disobedience. From the Chain of Unity to the reburial of Stus, Lytvyn, and Tykhyi, from the “Ukraine without Kuchma” protests to the Language and Tax Maidans, from “Save Kyiv” rallies to protests against the Protasiv Yar construction, and campaigns of reminding the public about the Ukrainian captives in the Russian prisons.

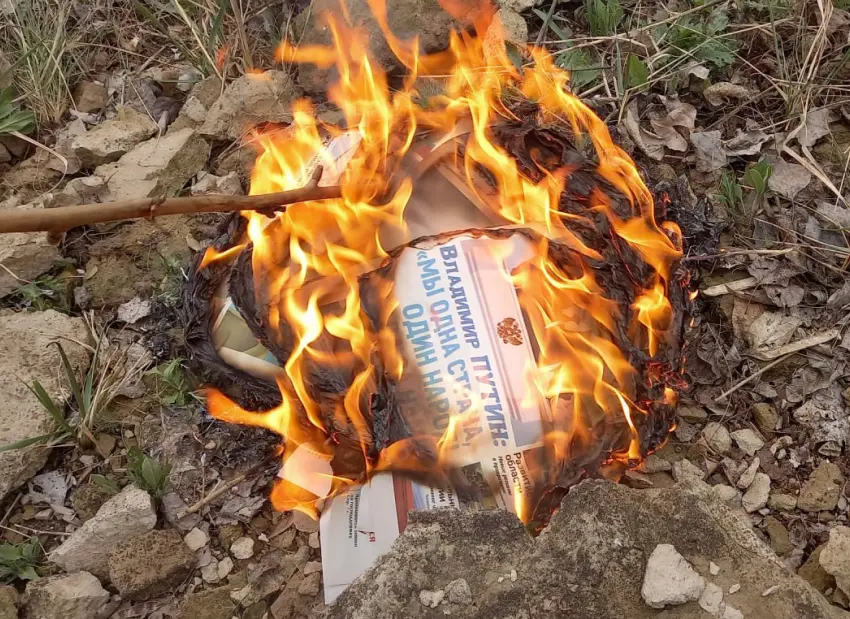

In the beginning of the full-scale invasions, many towns and cities of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts held mass protests against occupation. In the currently occupied territories, underground resistance movements like “Zhovta strichka” [Yellow Ribbon], “Zla Mavka” [Wicked Nymph], “Krymski boiovi chaiky” [Crimean Battle Seagulls], “Atesh”, etc. continue to resist Russian occupation.

The Yellow Ribbon underground movement continues to grow in the territories occupied by Russia.

In the photo: Leaflets of the movement on the streets of occupied Melitopol. Source

Non-violent resistance is now an organic part of modern Ukrainian society. A society free that is increasingly free from paralyzing fear, and filled instead with a strong sense of human dignity.

Read also